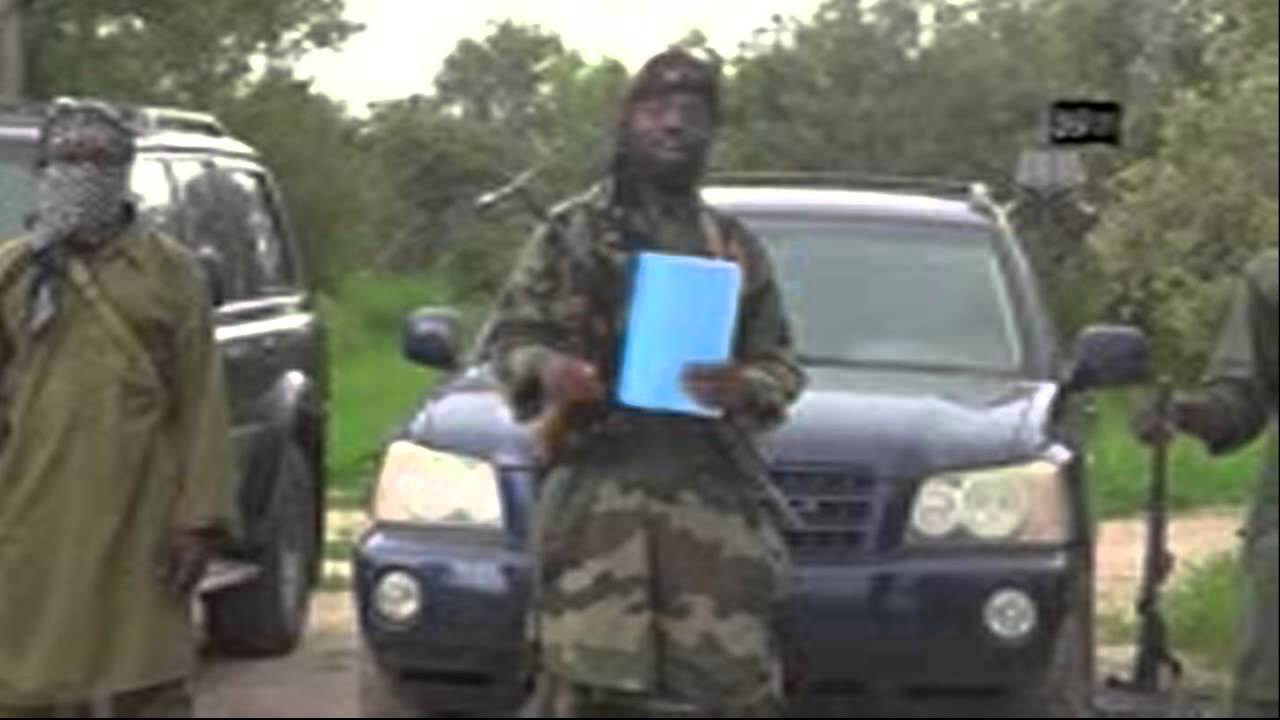

That the Nigerian government would broach the idea of negotiating with members of the Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’Awati Wal-Jihad otherwise known as Boko Haram, is too bitter a pill for many Nigerians to swallow. And understandably so given the havoc that this terrorist group has wreaked on the country and its psyche in the past couple of years.

In 2014 alone, the group was believed to have killed more than 10,000 Nigerians in addition to maiming thousands more and destroying property worth billions of naira. So, Nigerians are justifiably angry with the sect and would want the military to battle it until the last man is sent to rot in hell. Unfortunately, like a dying patient whose only chance for survival is hinged on the ingestion of some irritating concoction, Nigeria currently has little or no option than to negotiate with the deadly sect. In fact, prospects for negotiations seem to be the most inspirational suggestion from the six-week old government of President Muhammmadu Buhari.

I understand the sentiment of Nigerians who are angry at the suggestion but then, nations endure when they face their realities rather than wallow in emotional aspirations that their situations do not support. How exactly does Nigeria hope to defeat these insurgents militarily? True, some months back, multinational forces put together by Cameroon, Niger, Benin and Nigeria ravaged the camps of the insurgents like a vengeful plague. Daily, we saw videos of recaptured territories and a jubilant army celebrating their exploits. These victories, we understand, were due to the re-equipment of the Nigerian Armed Forces which invariably shored up the morale of our men and officers.

To yours truly, and I imagine, to a lot of other Nigerians, the routing of the insurgents in the weeks preceding the general elections was indicative of the end of the insurgency. But we were mistaken. In the past six weeks or so, not less than 500 lives would have been lost to attacks by Boko Haram insurgents or those who exercise their franchise. In these weeks, the North-East, which has borne the brunt of the warfare, the North-West and the North-Central have been shaken by deadly attacks with signatures identical with that of Boko Haram. The implication of this is that the military campaign between February and March this year has only succeeded in containing the insurgency to an extent but even that extent remains costly for the country unless something more positively drastic is done. And for a number of manifest reasons, which I will enumerate, I do not think those solutions could be military.

The first is that by the nature of insurgencies, military confrontations are never the ultimate solution. This fact is corroborated by examples from all over the world. Like we have in Nigeria, most insurgencies are trigged by socio-political disaffections. And as Jonathan Powell, the British diplomat who served as chief British negotiator on Northern Ireland argues, in a paper entitled, Security is not enough: Ten lessons for conflict resolution from Northern Ireland,” if there is a political problem at the root of a conflict, there has to be a political solution to it. Powell quotes Hugh Orde, a former Chief Constable of Northern Ireland, as saying that “there are no examples anywhere in the world of terrorist problems being policed out.”

There must, at some point, be some political solution as is evidenced in the Northern Ireland “Troubles” which was effectively on for about four decades before settlement was reached. Of course, Powell and Orde do not suggest that security measures have no place in dealing with insurgencies as they argue that without “security pressure, insurgents will find life comfortable and have no incentive to make the tough decisions necessary for peace.” But the point remains that “security pressure by itself without offering a political way out will simply cause the insurgents to fight to the last man.” I daresay that this is the situation that Nigeria currently faces. With an army of demoralised soldiers, a lot of whose motivation in the army, by the admission of the army chief is more pecuniary than militaristic, we cannot bank on terminating this insurgency on the war front.

The chance is worsened by the archaic state of our security architecture, infrastructure and intelligence gathering. How does a nation that relies on other nations, regardless of their own situation, hope to win this kind of war? But more than this, Nigeria’s ability to win this war through the guns is hampered by its guerilla nature. The size of Sambisa Forest, one of the strongholds of these insurgents, which spreads across Borno, Yobe, Gombe, Bauchi states makes it difficult to go all the way as civilian causalities will definitely be incurred. This is worsened by our pathetically porous and policed borders which allow aliens come wreak havoc on the country at will. The level of poverty in the country also makes the potential for Boko Haram recruitments very easy.

This is coupled with the deceptive religious toga which the insurgents have given to their war. A situation in which a 10-year-old girl gets nominated by her father to undertake a suicide mission tells the extent of local collaboration which Boko Haram could get as a result of the sale of lies whose potency is encouraged by the level of illiteracy and ignorance in the northern part of Nigeria. Most fatal to the chance of a military victory for Nigeria is the relentlessness of the insurgents. It is a venture at which perpetrators never stops reinventing and innovating.

At the start, Boko Haram attacked soft targets, visiting schools and worship places; over the years, it acquired a territorial status to the extent that more than 30 local governments in the North were under its control with its flag hoisted. But with the military incursions of the armed forces in the first few months of this year, Boko Haram has gone back to its initial strategy of attacking soft targets, mingling with people in worship places, restaurants and drinking joints and detonating explosives with massive casualties following. How does a nation, which cannot boast of high grade intelligence gathering, win such confrontations on the war front? How do we deal with situations in which bombers disguise as worshippers, only to unleash explosives on innocent worshippers? This is why the Federal Government must go ahead and do everything within its capacity to resolve the Boko Haram challenge. If we think about it, the risk involved in allowing the reign of violence to continue is enormous for the future of the country.

For instance, Northern Nigeria currently bears the burden of having the highest number of out-of-school children in the world. This is inadvertently preparing another generation of terrorists. And the greatest harm that we can do to the future of Nigeria is to allow these insurgents hand over to another generation which is likely to be more vociferous in their hatred for the nation than the current generation, in the same way in which the present Boko Haram leaders are more violent and deviant than Yusuf Mohammed who founded the group. This government must work hard to dismantle the pyramid of violence that insurgent groups have mounted in the country.