Nigeria, a country with a large domestic market of more than 160m people, spends huge resources importing consumer goods from China that should be produced locally. We buy textiles, fabric, leather goods, tomato paste, starch, furniture, electronics, building materials and plastic goods. I could go on.

The Chinese, on the other hand, buy Nigeria’s crude oil. In much of Africa, they have set up huge mining operations. They have also built infrastructure. But, with exceptions, they have done so using equipment and labour imported from home, without transferring skills to local communities.

So China takes our primary goods and sells us manufactured ones. This was also the essence of colonialism. The British went to Africa and India to secure raw materials and markets. Africa is now willingly opening itself up to a new form of imperialism.

The days of the Non-Aligned Movement that united us after colonialism are gone. China is no longer a fellow under-developed economy – it is the world’s second-biggest, capable of the same forms of exploitation as the west. It is a significant contributor to Africa’s deindustrialisation and underdevelopment.

My father was Nigeria’s ambassador to Beijing in the early 1970s. He adored Chairman Mao Zedong’s China, which for him was one in which the black African – seen everywhere else at the time as inferior – was worthy of respect.

His experience was not unique. A romantic view of China is quite common among African imaginations – including mine. Before his sojourn in Beijing, he was the typical Europhile, committed to a vision of African “progress” defined by replicating western ways of doing things. Afterwards, when he became permanent secretary in the external affairs ministry, the influence of China’s anti-colonial stance was written all over the foreign policy he crafted, backing liberation movements in Portuguese colonies and challenging South Africa’s apartheid regime.

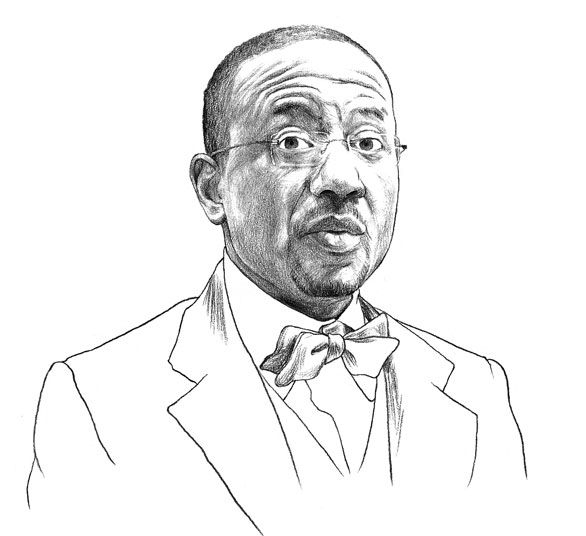

This African love of China is founded on a vision of the country as a saviour, a partner, a model. But working as governor of Nigeria’s central bank has given me pause for thought. We cannot blame the Chinese, or any other foreign power, for our country’s problems. We must blame ourselves for our fuel subsidy scams, for oil theft in the Niger Delta, for our neglect of agriculture and education, and for our limitless tolerance of incompetence. That said, it is a critical precondition for development in Nigeria and the rest of Africa that we remove the rose-tinted glasses through which we view China.

Three decades ago, China had a significant advantage over Africa in its cheap labour costs. It is losing that advantage as its economy grows and prosperity spreads. Africa must seize the moment. We must encourage a shift from consuming Chinese-made goods to making and consuming our own. We must add value to our own agricultural products. Nigeria and other oil producers need to refine crude; build petrochemical industries and use gas reserves – at present often squandered in flaring at oil wells – for power generation and gas-based industries such as fertiliser production.

For Africa to realise its economic potential, we need to build first-class infrastructure. This should service an afro-centric vision of economic policies. African nations will not develop by selling commodities to Europe, America and China. We may not be able to compete immediately in selling manufactured goods to Europe. But in the short term, with the right infrastructure, we have a huge domestic market. Here, we must see China for what it is: a competitor.

We must not only produce locally goods in which we can build comparative advantage, but also actively fight off Chinese imports promoted by predatory policies. Finally, while African labour may be cheaper than China’s, productivity remains very low. Investment in technical and vocational education is critical.

Africa must recognise that China – like the US, Russia, Britain, Brazil and the rest – is in Africa not for African interests but its own. The romance must be replaced by hard-nosed economic thinking. Engagement must be on terms that allow the Chinese to make money while developing the continent, such as incentives to set up manufacturing on African soil and policies to ensure employment of Africans.

Being my father’s son, I cannot recommend a divorce. However, a review of the exploitative elements in this marital contract is long overdue. Every romance begins with partners blind to each other’s flaws before the scales fall away and we see the partner, warts and all. We may remain together – but at least there are no illusions.

This article was first published in the Financial Times of London.