It’s easy to write off Nigeria as a place destined to squander the potential of Africa’s largest population and oil reserves. Under successive governments, corruption has flourished, poverty has increased and religious rivalries have festered. Since 2014 — the year Nigeria temporarily overtook South Africa to become Africa’s biggest economy — it has been crippled by the crash in crude prices and a renewed bombing campaign by militants targeting oil pipelines. It’s also battling the Islamist insurgency of Boko Haram, which has fueled humanitarian crisis that’s displaced as many as 7 million people. Meeting the needs of Nigeria’s 180 million citizens is only going to get tougher — the United Nations expects the population will more than double by mid-century, overtaking all nations bar China and India. Is Nigeria doomed?

The Situation

President Muhammadu Buhari, a 74-year-old Muslim from the north and former military ruler, took office in 2015 as the first opposition candidate to win a Nigerian election. The vote was seen as a critical test of Nigeria’s ability to hold a free and fair contest and break a pattern of violence, offering a chance for the nation to set a new course. Since then, his popularity has waned. Buhari spent more than seven weeks on sick leave in the U.K. in early 2017, fueling concern about government paralysis and speculation he won’t be able to complete his term. The economy shrank for the first time in 25 years in 2016 and inflation soared to 18.5 percent. The crash in energy prices was always going to make Buhari’s job tough. But critics say his refusal to allow a weakening of the currency, the naira, made a bad situation worse, sending foreign investors fleeing and creating a shortage of dollars to pay for imported goods. Buhari has tried to clamp down on corruption while driving back Boko Haram in the north and grappling with renewed violence by rebels in the oil-rich south.

The Background

The ethno-religious rivalry is a legacy of colonialists who bundled a Muslim-ruled north with the south’s majority Yoruba and Igbo Christians to create Nigeria in 1914.

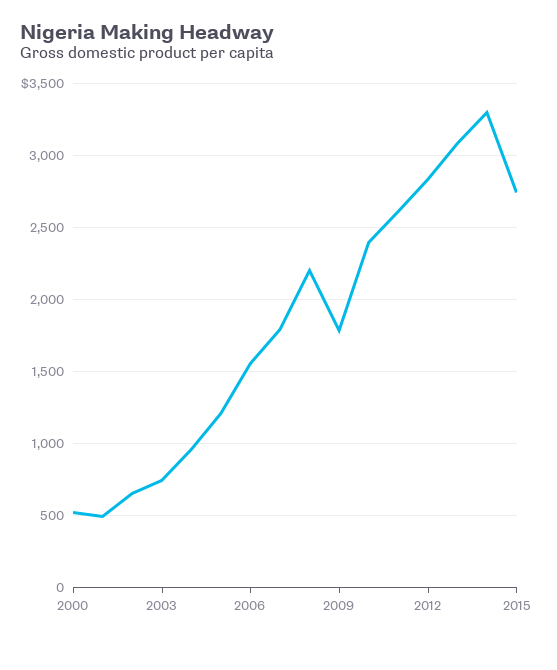

In the north, the British ruled indirectly through emirs, while in the south they had a tighter grip and allowed missionaries to spread their religion. Today, more than half of people in the north live in poverty, while the south is endowed with all of Nigeria’s oil wealth and Lagos, the main commercial hub and home to 15 million people. High oil prices sent Nigeria’s economy soaring from 2000, though inequality is stark. Weak governance and poverty in the north bred resentment that gave birth to Boko Haram, whose campaign of terror since 2009 has led to the deaths of more than 20,000 people. The jihadists captured world attention in 2014 when they kidnapped 276 schoolgirls in the village of Chibok.

The conflict has spilled over into neighboring countries such as Cameroon and Niger, which have worked together to push back the militants. Pipeline bombing by a different group of rebels in the Niger River delta, along with kidnappings and pirate attacks, have driven investors such as Shell and Chevron to divest from onshore oil fields and focus on easier-to-secure installations off Nigeria’s coast.

The Argument

To optimists, rising incomes and a surging, young population give Nigeria the potential to follow in the footsteps of hot emerging markets like India or China. That could spur development and provide a model for African democracy.

But first the country needs to curb corruption and improve slow and inefficient institutions such as the judiciary and the civil service. Nigeria must to overcome its divisions and improve basic service, as the vast majority of its people live without regular access to electricity and have poor schools and hospitals.

Fewer petrodollars might drive the development of manufacturing plants and help Nigeria break out of the so-called resource curse. What is certain is that Nigeria is too big and important for the rest of the world to ignore.