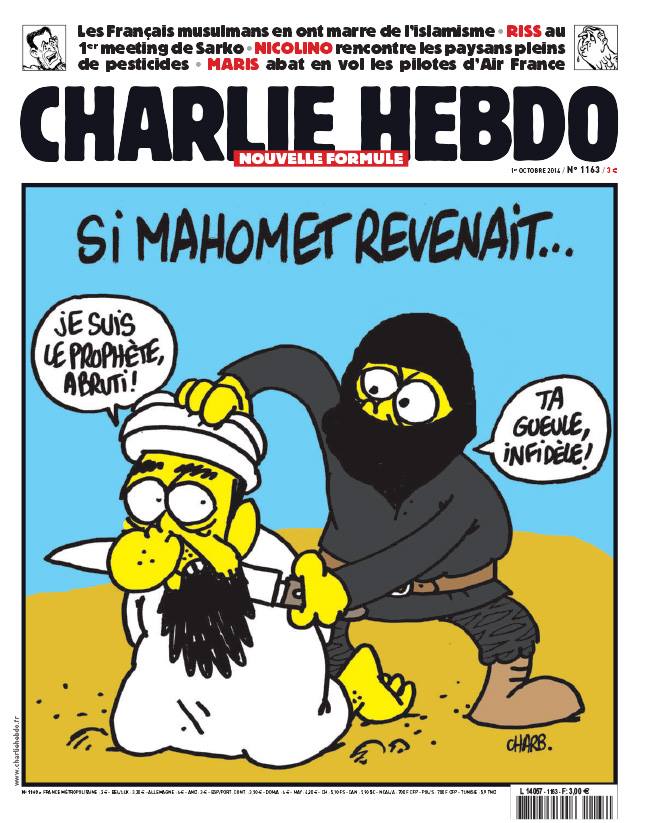

IN the aftermath of the January 7 Islamist terrorist attack on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and a separate but apparently related January 9 attack on a Jewish supermarket, both in Paris, over three million demonstrated throughout France in solidarity against terrorism. In Paris, demonstrators numbered some 1.6 million.

There were also companion demonstrations in London, Washington, and other cities. Europeans are comparing the trauma caused by the attacks as similar to that of 9/11 in the United States. According to the New York Times, President Francois Hollande was joined by more than 40 heads of government or heads of state, including German chancellor Angela Merkel, Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, Mahmoud Abbas of the Palestinian Authority, and many African heads of state. (The absence of high-level Obama administration representation is curious.)

On January 10, at a market in the northern Nigerian city of Maiduguri, a suicide bomber, a girl perhaps as young as 10 years of age, killed herself and at least 20 others and wounded an unknown number. On January 11, two female suicide bombers, one perhaps 15 years of age, killed themselves and four others in the city of Potiskum, according to Agence France-Presse. Potiskum is in northern Nigeria’s Yobe state. Borno and Yobe have long been venues of Boko Haram operations. However, the militant jihadist movement has as yet not claimed responsibility for either attack.

Earlier in January, Boko Haram defeated the Nigerian security forces at Baga. The fighting, and a subsequent Boko Haram massacre, resulted in at least 2,000 deaths.

Boko Haram and the French militant jihadists use a similar rhetoric. Yet the attacks in France and Nigeria are almost certainly unrelated. Instead, both reflect the unique circumstances where the attacks took place. France was the colonial power that dominated North Africa and Syria. France has Europe’s largest Muslim population, mostly of North African origin. Its integration has been difficult and incomplete. The killers in France appear to have been French citizens of Algerian origin, and some may have been trained by al-Qaeda affiliates. In Nigeria, Boko Haram flourishes in a predominately Muslim part of the country that is poor (and getting poorer), perceives itself as politically marginalised, and is open to radical Islamist influences. Ties between Boko Haram and international jihadist movements appear to be weak.

Total casualties from the January 7-9 attacks in France were 17, and in Nigeria the suicide attacks seem to have claimed about 26. Killings in northern Nigeria associated with Boko Haram since May 2011 number at least 10,501, according to the Council’s Nigeria Security Tracker. Yet the killings in France now dominate Western discourse, while the little attention devoted to those in Nigeria is focused on the sensational use of child suicide bombers. The difference in Western attention commanded by the two is not entirely media bias. The attacks in France go directly to the core Western values of freedom of expression, and they took place in one of the West’s greatest cultural capitals. (As Thomas Jefferson allegedly said, “Every man who loves liberty has two countries, his own and France.”) The attacks also play on anxiety generated by non-European immigration. By contrast, the Boko Haram attacks occur in an isolated part of Africa, far even from the Nigerian metropolis of Lagos. Further, in Nigeria, Boko Haram appears to be (among other things) engaged in a civil war against other forms of Nigerian Islam. In the context of upcoming national elections, its attacks bear little relevance to people outside northern Nigeria – even in Lagos.

That said, there is no question that the use of child suicide bombers in northern Nigeria is a new threshold of horror.

International assistance for Nigerian refugees

In the best of times, Northeastern Nigeria and the adjoining regions in neighbouring Chad, Niger and Cameroon are among the poorest regions in the world. Food security, especially, is highly fragile in the face of desertification and overpopulation. These are not the best of times.

In areas where the radical, Islamist movement called Boko Haram operates, there has been little or no planting or harvesting of food, in some cases for up to three years. Fighting between Boko Haram and the Nigerian security services has displaced many residents of these farflung regions in the north. The number of iternally displaced people (IDPs) is not known, but some credible estimates put the figure at more than one million. Most IDPs are taken in by family, and some receive assistance from the Nigerian Emergency Management Agency (NEMA).

Legally, IDPs are the responsibility of the Abuja government. Once displaced individuals leave Nigeria, however, they become refugees and the responsibility of the international community, particularly the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as per various UN agreements and protocols. This month, the UNHCR reported that some 7,300 Nigerians have fled to Chad as a result of Boko Haram’s recent campaigns in and around the border town of Baga.On January 8, Chad’s prime minister appealed for more international assistance to enable his government to respond to the refugee flows. The UNHCR has agreed to assist with the relocation of refugees who became stranded on islands in Lake Chad while attempting to flee Boko Haram. The UNHCR estimates that more than 10,000 Nigerian refugees have ended up in Chad due to the fighting in Baga and previous Boko Haram attacks in the neighborhood.

Niger may have more Nigerian refugees than Chad. A census carried out by the Niger government with UNHCR technical support found that at least 90,000 refugees have arrived in one Niger region since May 2013. (That figure includes many Niger nationals who had been living in Nigeria.) The UNHCR and the National Eligibility Commission of Niger have established a refugee camp, in which some refugees have been documented and basic relief, including drinking water and latrines, supplied.

There are likely to be many more refugee camps in the future if Boko Haram’s terror campaigns in the north continue unabated.

Africans have a long and honorable history of taking in refugees, often with little cognizance by central government authorities. That seems to be especially true of the response to Nigeria’s IDPs. Yet, refugees fleeing Nigeria are an international responsibility and it is only a matter of time before the international community will need to ramp up its support for the UNHCR and for other relief agencies such as the World Food Programme to respond to the humanitarian disaster growing quietly in northeast Nigeria.

Campbell, a former United States Ambassador to Nigeria, posted this on cfr.org/campbell.