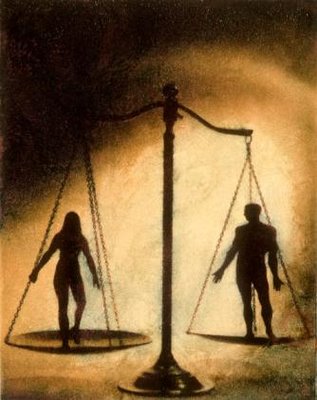

The media remains the veritable tool for real and genuine general development. This is because of its awesome influence and impact on other catalysts for growth and economic development. One of such strategic areas of power and authority is agenda setting for policy makers and the entire human race. Therefore, there is the incontrovertible need for the society to strike a balance in gender representation in such a powerful, dominant and potent organ.

Despite the recent seeming global campaign, the media in Sub-Sahara Africa is still dominated by the male folk. The prevalent trend is owing to some unspoken policies by the management of most media organizations, based on stereotypes and not in any way on the competence, integrity, ability and capability of female journalists. Some influential senior practitioners usually exploited the said policies to suit their personal whims and caprices on the pretext of protecting the interest of their principals [owners] diverse interests—economic, political, cultural and societal. They deliberate create barriers and demarcation as to where, role and extent female journalists could go or operate in the daily activities of the media, thus an unnecessary compartmentalization, rigid departments and segments that inhibit the operational milieus of female journalists.

Stereotypes

Most critical beats are assigned to male reporters. One of the reasons is the fact the key managers saddled with allocation of beats are men, who intuitively believe that ‘sensitive’ areas must be handled by men and not women. In effect, women are considered as the weaker sex, who lack the physical capacity to cope with very rigorous assignments and events associated with some so-called sensitive beats. Vital issues of competence, ability, professionalism and resourcefulness are not often given priority by some top editorial members in the allocation of beats to female practitioners. Thus, such areas like defence, judiciary, crime, politics, aviation maritime, just to name a few vital sectors are hardly assigned to female journalists, particularly in Sub-Sahara Africa.

There is equally a stereotype that bothers on womanhood. The thinking among most news managers is that Nigerian women belong to the kitchen, even if she is a career woman and professional. She is expected to quickly return to the kitchen after closing from their place of work and combine the duty of a house wife with that of a mother cum quasi-house keeper. Unfortunately, a lot of the female media practitioners acquiesce to the weird role and perception. They do not only express satisfaction with their establishment for saving them from the ‘rigours and ordeals’ of challenging the status quo-proving that they can excel in those core betas, if given the chance but also set a new standard in news reportage and other media operations/activities. Some female practitioners are ecstatic that not-too-stressful beats afford them the opportunity to deploy their energies in other personal adventures, which are often mundane and frivolous. In order words, some female practitioners are their own enemies, and not necessarily their masters in the office. Of course, their spouses could regard as accomplices as they do not see anything wrong with such complex towards the career of their wives.

Self-inflicted problem

A related issue is the obvious preference of the female practitioners for certain beats that their male counterparts hardly show enthusiasm. Though those beats are critical to the existence of humanity, they are regarded as not as challenging like others, which by their own estimation, are more hazardous, energy sapping and non-lucrative. So, there are still more female practitioners handling only women and children ‘issues, as well as fashion and style, and not sport, politics and economics, for example. So, female practitioners are seen as beautiful faces that should drive entertainment pages, irresistible figures with vital statistics that should adorn the pages on fashion and style in news papers and magazines. What all this means is that they are seen as sex symbols/objects and not as core professionals with inimitable intelligence, creative endowment and zeal, who can excel in areas of the media industry if given an equal opportunity and exposure. .

Economic challenges

The battle for gender equality is also facing a lot of challenges because of cultural milieu most female practitioners have found themselves, especially in Sub-Sahara Africa. Various cultural restraints impede female media practitioners from realizing their full potential. Unbridled emotional attachment to culture in Nigeria, for instance, inhibits a female journalist in so many ways in harnessing her potentialities as a professional like her male counterparts. The issue of religion constitutes a sensitive matter and often limits access by a female media practitioner, as her faith strictly defines how far she can go in relating with some sources in discharging her duty. In some circumstances, she is largely required to be seen and not heard, notwithstanding her professional background, pedigree and competence.

Economic realities have imposed new constraints on her in Nigeria. The appalling state of the national economy has created more serious challenges at the home front such that she must device other means of augmenting her official income in order to survive. Sometimes her professional practice becomes subsumed as she must join others if she can’t beat them in the pursuit of money and other mundane things of life. In many cases, they have to combine their office work with private businesses such as buying and selling. Thus, she prefers those beats that she considers as likely to give her the chance to engage other means that can provide additional money or income, without consideration for the far-reaching implication of the divided interest on her career in terms of self-development, progression and job satisfaction.

New approach

On the whole, the crusade for gender equality in the media requires a more pragmatic approach, which must include proper mental re-orientation among female practitioners. There is the need for total re-awakening, consciousness and attitudinal change. The battle against stigmatization must be sustained, aggressive and pragmatic, especially within the corridors of media organizations, so that those directly responsible for the gender inequality can appreciate enormity of their act of injustice to female practitioners.

The current crusade must be more intense, intensive and pronounced among professional groups in the media industry. The campaign should take a multidimensional approach with well-designed messages and slogans targeted at different segment of the audience.